‘You can’t buy my grandfather, and you can’t borrow him. But if I give him to you, for safekeeping, you’ll make his death mean something?’

‘I can’t promise you that Timothy.’ There was no way I could swear to something so enormous and imprecise. ‘We don’t know what the book will reveal. And I certainly can’t guarantee that anything will change.’

‘Can you make sure his name won’t be forgotten, once you learn what it is?’ Timothy asked. ‘Names are important, you know.’

One of my favourite things about the All Souls books has always been (quite obviously given this blog…) their depiction of art and material culture more broadly. From my first read, Deb Harkness’s descriptions of Diana consulting manuscripts in the Bodleian hooked me. It reminded me of everything I love about working with manuscripts and studying manuscripts and art history – the challenges of working in the past, the feel of vellum, the smells, and the weight of the responsibility of doing justice to the objects and people you are writing about. At a point when I loathed my research more than I loved it, I was reminded of all of this so vividly. To say I’m partial to the books and their descriptions of manuscripts is a bit of an understatement. Yet, when I – like so many others – heard about the TV show, I was so excited to see how all of this was going to play out on screen. And so far, I have loved it. (Side note: apologies (of the sorry, not sorry, but also sorry sort) to all my non-fan friends and colleagues who’ve had to deal with me in a constant state of excitement and shouting at them to read the books/watch the series!) But, and this is a kind of important but, there are some issues, shall we say, with the handling of manuscripts in the first episode. I brushed them off, being familiar with the “correct” way of doing it, how amazingly Deborah Harkness captures this in the books, and having some idea of the effort that went into the production for authenticity. But seeing some colleagues talking on Twitter and conversations with friends offline got me thinking about manuscripts, their portrayal in the series (both book & TV), and their materiality.

I’m going to break the portrayal(s) down in terms of manuscript handling first. Then, I’m going to make some observations about the materiality. There will be spoilers because aspects of Ashmore 782’s materiality is key to how the narrative unfolds – and you do not necessarily realise it until the end. In fact, the second half of this post is rather spoiler-y.

Ashmole 782 is key to the story. In so many ways. But what is Ashmole 782? It is a real manuscript, and has been missing for over 100 years. We have a catalogue entry that describes it as: ‘Anthropologie, or a treatise containing a short description of Man in two parts: the first Anatomical, the second Psychological.’

In the book, Diana knows from the moment she encounters the manuscript that something is up. She goes on to describe how she tries to confront it before describing how she consults it. (The quotes throughout are from Chapter One of A Discovery of Witches.)

The manuscript that had appeared to tug on its call slip lay on top of the pile… I reached out, touching the brown leather. A mild shock made me withdraw my fingers quickly, but not quickly enough. The tingling traveled up my arms, lifting my skin into tiny goose pimples, then spread across my shoulders, tensing the muscles in my back and neck. These sensations quickly receded, but they left behind a hollow feeling of unmet desire. Shaken by my response, I stepped away from the library table. Even at a safe distance, this manuscript was challenging me.

The shock described here is visualised through Diana’s handling of the manuscript – and the manuscript’s response to her as it marks her skin at one point.

Many of the concerns I have seen and heard revolve, as noted, around handling Ashmole 782 and the other manuscripts Diana consults in Duke Humphrey’s. The plastic book cradle. The way she unsticks the folios. The light shining directly on the folio. And then laying her hand directly over the illuminated (not just illustrated) image. Then slamming it shut and all but throwing it back at the desk and running out of the Bodleian. Now, admittedly, these things aren’t great. And the book isn’t as hurried in its descriptions of what is happening. I also have some thoughts as to why – despite knowing that Teresa Palmer (Diana) was trained in handling manuscripts – it’s shown like this.

To break it down:

The plastic book cradle: Do I wish the libraries I was in had plastic cradles? Not really, though, they are nice… Normally, it’s a bean bag-like cushion that you carefully shape to support the manuscript you’re looking at, or a set of foam blocks that you build up into a shape that best supports your manuscript. These comparatively soft cradles help support the binding of the manuscript without taxing it. If the binding is loose, then you adjust your cradle to accommodate that. If the manuscript’s binding is tighter, you adjust, building up your cradle. And, we don’t normally just let the manuscript stay open on its own. If anyone is looking at a folio for more than a second, we have these lovely weights called snakes that drape over the folio – strictly on the outer edges – to keep it open. So, what’s happening here? I think it’s largely two-fold: I don’t think she really needs snakes for most of the scene. Granted, while she’s typing out descriptions, yes. But while she’s looking at the page and interacting with it, nope. That cradle, though! That has to be an image choice: plastic that shows the manuscript binding just looks better on screen than the (beloved) cushions.

The unsticking of the folio: Right, I do not know a single manuscript person that doesn’t gasp/cringe to some extent at this moment. We’ve all had sticky or uncooperative folios. But it’s always careful handling and get an archivist if necessary. No forcing apart. No, no, nope. So where does this come from? It’s in the book. Well, kind of. Initially, Diana notes that it is the cover that will appears as if it is stuck. She has to lay her palm flat on the leather binding so the manuscript gets to know her:

It was difficult to lift the cover, despite its loosened clasps, as if it were stuck to the pages below. I swore under my breath and rested my hand flat on the leather for a moment, hoping that Ashmole 782 simply needed a chance to know me. It wasn’t magic, exactly, to put your hand on top of a book. My palm tingled, much as my skin tingled when a witch looked at me, and the tension left the manuscript. After that, it was easy to lift the cover.

So, while most of us don’t just touch the covers for the fun of it (because covers and bindings can be just as fragile as the folios they contain!), in context, it’s a bit more understandable. The manuscript – bewitched – needs to recognise her. (Spoiler: It’s bewitched to recognise her only when she *needs* it. And you’ve seen who bewitched it in this episode…) The show, I think, is trying to show this moment in a way that makes sense for it visually: the manuscript is a problem for Diana. It’s a literal sticking point for her: magic, scholarship combine and she has actively denied the magic in her scholarship, or thinks she has. This works slightly better visually with folios rather than the cover. Bonus: it lets us see the folio after the alchemical child, too!

The light on the folio: I recall seeing this in the trailer and commenting to a friend that I wish I could do that because it could tell me something about the folio/manuscript I was working on at that moment. Would I? Umm, not without permission. Why? Because light (and a host of other things) can damage manuscripts, some worse than others, to be fair. There’s a reason some are always kept in low light and only on display in special cases. Think Book of Kells in Trinity College Dublin. Think watercolours in any number of museums. Think the British Library Treasures Room light levels. Colour is fragile. Thousand (plus) year old parchment/vellum (aka skin) is fragile. As we study these objects, we’re also taught to protect and care for them.

I, however like others, have noticed things I most likely would not have when the light caught a folio I was turning. In one case it was the movement showing me how the gold reacted on a folio to obscure part of the imagery. In another, more similar to what Diana experiences, it was the hint of something below the text. It turned out to be the paper’s watermark. I admit to holding it so that the light in the room caught it better to take a photo. There were no individual lamps in the space, so shining a light on it wasn’t an option – and if there were, and I did, I can imagine the librarians on duty rushing over to ask just what I was doing. So, yes, light is hugely important, but it’s also a bittersweet importance. We only rarely get to interact with these manuscripts in light conditions that reflect the original viewing conditions. (Liturgical manuscripts by candlelight, for instance. Because open flames near manuscripts is enough to send even the most laid back researcher into heart palpitations.) And sometimes film and TV can do to prop manuscripts what we only dream of doing to actual manuscripts, which makes them exciting (if occasionally frustrating) bits of experimental archaeology.

So, Deb does describe this in the book, and acknowledges how you have to have the perfect angle of light, and sometimes the perfect technology, to reveal a palimpsest.

I searched for something – anything – that would agree with my knowledge of alchemy. In the softening light, faint traces of handwriting appeared on one of the pages. I slanted the desk lamp so that it shone more brightly. Words shimmered and moved across its surface – hundreds of words – invisible unless the angle of light and the viewer’s perspective were just right. I stifled a cry of surprise.

And I didn’t think twice about this while reading it – partly because it’s something I’d always wondered about combined with knowing how much a different angle with the light source can reveal. And in the show, I think what is a simple description is heightened because it’s visual and it’s done in a way you cannot brush it off. Why? Because you have to understand that this manuscript is a palimpsest. And it is broken. Words don’t run across a page. Or, well, they shouldn’t… And recognising that Ashmole 782 is a palimpsest is key to the overall narrative. It is connected to Diana, and it is important to note that she becomes part of its palimpsest in this scene: it’s the viewer’s first tangible clue that maybe it is Diana that the manuscript is reacting to – and not just reacting because she is a witch. There’s a whole lot to say about the palimpsest and materiality here, and I’m going to talk about this more below because major(ish) spoilers, but for now, I think they’re showing this with the light to reiterate this: it is a palimpsest, Diana is connected to it, and it has to stand out.

Touching. The. Page: Manuscript Handling 101 is that you touch the edges or the corners. And. Not. The. Image (or text). Why? Well, simply, because things flake. The oil on your hands can damage the pigments, too. And that’s without you doing anything but opening the manuscript. Pigments and ink can be very unstable when they’re that old. (And no, we don’t wear gloves unless there’s a really really good reason. You’re more likely to tear or otherwise damage the manuscript as you lose some dexterity with gloves.) In the book, Diana goes out of her way to talk about how she does not touch it because it could tell her something more than a human scholar should know.

My fingers wanted to stray back and touch the brown leather. But this time I resisted, just as I had resisted touching the inscriptions and illustrations to learn more than a human historian could legitimately claim to know.

Why, then, does Show Diana touch it? I think partly because she’s terrified and just wants it to stop. We know she’s uncomfortable with magic. She then sees that the manuscript is a palimpsest. But it’s not just a palimpsest. It’s a magical one, with hidden words that *move.* She slams her hand down because she wants, needs, it to stop. She needs it to be just another alchemical manuscript. It isn’t (or this would be a quick book/series), and she has no idea how to handle that. A palimpsest she can handle. Magic she can (pretend to) handle. Together? That’s a giant nope. But her curiosity is winning here – she wants to find out more, at least as a scholar. She’s in denial as a witch, for now.

Even more importantly, here, is (damn you spoilers and trying to avoid them) what this manuscript will come to represent for her, for the story, and for the world of creatures. (I’m gonna address this much more in the spoiler-y section below.)

Running out of the Bodleian: Okay, this isn’t cool, but, again, I think we can understand why Diana does this: she needs away from the magic the manuscript represents. It’s a bit more innocuous in the book than on screen, to be sure.

I packed up my computer and notes and picked up the stack of manuscripts, carefully putting Ashmole 782 on the bottom. [Diana returns the manuscripts to the desk, requesting to keep three, but not Ashmole 782.] Sean put it on top of a pile of returns he had already gathered. He walked with me as far as the staircase, said good-bye, and disappeared behind a swinging door. The conveyor belt that would whisk Ashmole 782 back into the bowels of the library clanged into action. I almost turned and stopped him but let it go. My hand was raised to push open the door on the ground floor when the air around me constricted, as if the library were squeezing me tight. The air shimmered for a split second, just as the pages of the manuscript had shimmered on Sean’s desk, causing me to shiver involuntarily and raising the tiny hairs on my arms.

Again, I think the show is heightening her discomfort and, frankly, it’s fiction, and we all know that you can get away with a bit more in a TV show than in real life (or in a book). I do think, though, the show does a great job in this scene showing and hinting at things that make up the larger narrative of the story.

But then, later in the show, she leaves a manuscript open and walks away as the library lights are turned off, declaring her need for a drink. Right, again, every scholar I know has spent a day in some library only to desperately need a drink (and/or food) after. But, I promise, we normally carefully pack our things away, return the manuscripts, and then leave the library. We do not leave the manuscripts open (nope!) and sitting in their cradles, hoping they’ll be just like that when return, and just leave as the lights are turned off. Even when Diana hurries out of the Bodleian in the books, she does observe the traditions here, packing her things, returning her manuscripts, chatting when necessary, and then retreating from the library. She even comments that this is a hindrance in escaping the library and the creatures in it at least once. (Chapter 2: ‘Having observed the last scholarly propriety of exiting the library, I was free.’ And sometimes it does feel like freedom even while scholars recognise their privilege in getting to handle and work with manuscripts.)

The Materiality of Ashmole 782 & Manuscripts

I’m going to pretend anyone reading this is okay with spoilers about where the show is going in terms of narrative. If you’re not, then stop reading and come back at the end of the series (maybe in a few years after we get through the trilogy…). Seriously, if you don’t want spoilers, stop now. I’m going to try to keep it to a minimum, but only just. So, stop. Unless you’ve read the books (and seen the first episode), then continue on. Or don’t care about the spoilers. (If this is you, I reference without explaining some narrative details. Sorry if it makes no sense. Just ask me to explain in the comments or in a note & I will.)

Still reading? I don’t want any complaints…

One of the things I am loving about this show is how the materiality of manuscripts – and this one magical manuscript in particular – is coming to life. Literally. The Book of Life, aka Ashmole 782, we later learn is made of creatures: humans, daemons, witches, and vampires. They are all used in the making of this manuscript. Actual manuscripts, while not made of supernatural skins, are made of the skin of animals. Vellum and parchment are the principle material in the West throughout the Middle Ages. Starting in the 16th century (actually earlier, but just go with me here), paper becomes more popular, and a lot of alchemical manuscripts are on paper. But those that aren’t on paper, are on skin. Pigments are natural and man-made, including vermillion made during the alchemical process. The blood of bugs, crushed leaves, powdered stone, bone: it’s all there.

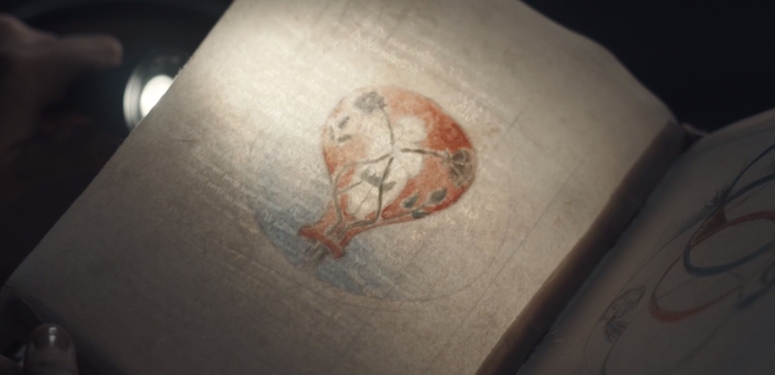

Ashmole 782’s materiality, we learn, is that of skin, blood, and the bones of creatures. Like its non-magical counterparts, the physicality of the world becomes artistic elements. When Diana records her general observations on the manuscript in the book she notes that it is both paper and vellum. It’s a mix and this is something that is incredible. Even before they get the missing folios into a lab to test, she’s aware that it’s mixed media in terms of folios/pages. Now, the knowledge that it is made from a mix of creatures does, admittedly, come later. But, it’s all reflected in her initial observations: it’s weirdly heavy, it smells strange. (Manuscripts do have strange smells because they’re made from animals and some of the pigments flat out stink – and that smell doesn’t always go away…) While the show does not describe the smell, visual mediums haven’t figured out how to show this quite the same way a written medium can, it does echo the key parts of that initial description: three folios are missing, the first image is of the alchemical child.

As I turned the first page, the parchment felt abnormally heavy and revealed itself as the source of the manuscript’s strange smell. It wasn’t simply ancient. It was something more – a combination of must and musk that had no name. And I noticed immediately that three leaves had been cut neatly out of the binding. Here, at last, was something easy to describe. My fingers flew over the keys: ‘At least three folios removed, by straightedge or razor.’ I peered into the valley of the manuscript’s spine but couldn’t tell whether any other pages were missing. The closer the parchment to my nose, the more the manuscript’s power and odd smell distracted me.

And when the knowledge of how weird the manuscript actually is does arrive? Oh boy. The scientists working with Diana to solve the mysteries of Ashmole 782 have loads of questions to answer. Also, it gives us keen readers some questions, too. The folios change weight. Why? (Guessing this is because the spell and the manuscript are both “broken.” As the words appear and disappear, the weight changes. As the magic ebbs and flows, the weight changes.) We do not know the exact ratios of creatures in the manuscript: is it equal? Is it mostly daemon? Mostly vampire? Is one skin more prized than the others? If so, why?! Are the colours made from the mixing of the different creature blood? (Another guess here: YES. Based on experiments in Mary Sidney’s lab in Shadow of Night, we know that the alchemical tree sprouts silver and gold when vampire and witch blood are mixed in the alembic. And I’m sure the scribe/artist/alchemist who made Ashmole 782 knew this, too, and used it to his/her advantage.) Suddenly just why everyone wants this manuscript is made even more evident: it does contain all the knowledge of the creatures.

So, what about what we do know in the show?

Let’s start with the heartbeat Diana hears. In the book, Diana notes the manuscript sighing.

I held my breath, grasped the manuscript with both hands, and placed it in one of the wedge-shaped cradles the library provided to protect its rare books. I had made my decision: to behave as a serious scholar and treat Ashmole 782 like an ordinary manuscript. I’d ignore my burning fingertips, the book’s strange smell, and simply describe its contents. Then I’d decide – with professional detachment – whether it was promising enough for a longer look. My fingers trembled when I loosened the small brass clasps nevertheless. The manuscript let out a soft sigh. A quick glance over my shoulder assured me that the room was still empty. The only other sound was the loud ticking of the reading room’s clock. Deciding not to record ‘Book sighed,’ I turned to my laptop and opened up a new file. This familiar task – one that I’d done hundreds if not thousands of times before – was as comforting as my list’s neat check marks. I typed the manuscript name and number and copied the title from the catalog description. I eyed its size and binding, describing both in detail.

I think we can all agree a manuscript that sighs is weird. And that it would give any scholar a bit of a worry. And any viewer might (would) be confused. However, by changing this to a heartbeat in the show, it gives it a dramatic depth. Diana looks around, confused by what she is hearing. We cut to Matthew sensing (hearing?) something that is clearly off. But we do not know yet that the manuscript is made of creatures (at least not of the usual cow or sheep sort), and Diana doesn’t register the smell as something that could tell her more about the manuscript’s materiality. We haven’t gotten there yet, because Diana has not grown into the witch she will become, and thus, she does not think about asking why it smells weird – it just does because manuscripts smell different. (It’s like an old book smell but more.) It’s magical, and she needs to ignore that part so she can describe it like any normal (read: human) scholar.

But there is more to this. Overwhelmed with what she hears and what she sees – I mean, the manuscript is putting words onto her hands and when she isn’t even touching it – Diana slaps her hands over the image. The result is that she is burned by it: an image of the alembic appears on her skin. The skin of the reader is transformed by the skin (albeit magical skin) of the manuscript. Marked creature skin marks witch (weaver) skin.

When I saw this scene in the trailer, I was beyond excited. (Spoiler warning reminder…) In the books, we know the manuscript is weird, and we eventually learn that the Book of Life basically chooses Diana to absorb its knowledge. She becomes the manuscript quite literally, and her appearance is changed because of it. Images and words appear on her; the words will move across her skin in answer to any questions posed to Diana. Having the book literally mark her in the first episode is a fantastic way to foreshadow this moment – and to alert the viewer that it’s magical and connected to Diana for reasons we do not (yet) understand.

Moreover, in terms of the materiality of manuscripts more broadly, it’s an amazing moment. The manuscript – usually a silent, inactive, passive object that scholars debate and talk about as object suddenly becomes so much more. It has agency: it marks Diana. She does not mark it. (Though her father has marked it since he’s responsible for the second hand on the opening page.) The manuscript rejects the scholar’s attempt to understand it by marking her and forcing the witch to confront her magic. (To be fair to Diana, it isn’t entirely her fault that she has struggled with magic. She is spellbound, after all, for her own protection.) It refuses to be sidelined and demands that Diana confronts it, setting off a chain of events that makes Diana, and the world of creatures, confront what they think they know about each other and themselves.

When we see manuscripts on screen, read about them in books, or consult digitisations, it can be easy to forget their physicality and materiality. Their size can be obscured. Their smell is certainly not obvious. The way they feel is exchanged for a modern book, a mouse, a hard screen. But, despite its faults, A Discovery of Witches is helping us bridge that gap but reminding us that manuscripts are more than our observations. They contain information we seek to unlock, and if we listen and observe carefully, they may reveal it to us. While no scholar should ever slam shut a manuscript or abandon it open on the desk, scholars do need to recognise and remember the materiality of manuscripts. (Hopefully without manuscripts burning our skin!) Natural elements – skin, plants, bugs – are manipulated into writing surfaces and inks. Nature dictates how we interact with them. Sunny days in the library can literally shine more light on a page than a cloudy, dark day. Monks and artists had to harvest pigments and turn them into viable inks. The weather dictated much of this: a bad winter or summer could kill your crop and leave you short (speaking from experience here!). The skin needed for a project may not be found in the quality preferred. (Not all vellum/parchment is created equally!) Seeing the materiality of Ashmole 782 and thinking about the hypothetical creatures that were involved in making (and rediscovering it), reminds us that manuscripts are more than simple books. They’re skin and blood.

In the All Souls world, they were somebody. Not just somebody’s creation but some body, as Timothy tells us in the starting quote from the third book in the All Souls Trilogy, The Book of Life. He recognises that the folio is someone – his grandfather (side note: I have so many thoughts on the age of Ashmore 782 and this that I am not even sure where to begin) – and entrusts the folio to Diana, as long as she remembers his name. By doing so, he asks her to remember that the folio is made from someone, and remember its materiality. Even seemingly simple scenes such as this force Diana – and through her, the reader – to confront Ashmole 782’s materiality.

And once we do, we have to acknowledge the materiality of art and manuscripts more broadly.

And that’s why I can’t wait to see what happens next in the show.

2 thoughts on “A Medievalist’s Thoughts on Manuscripts & Materiality in Episode 1: A Discovery of Witches”